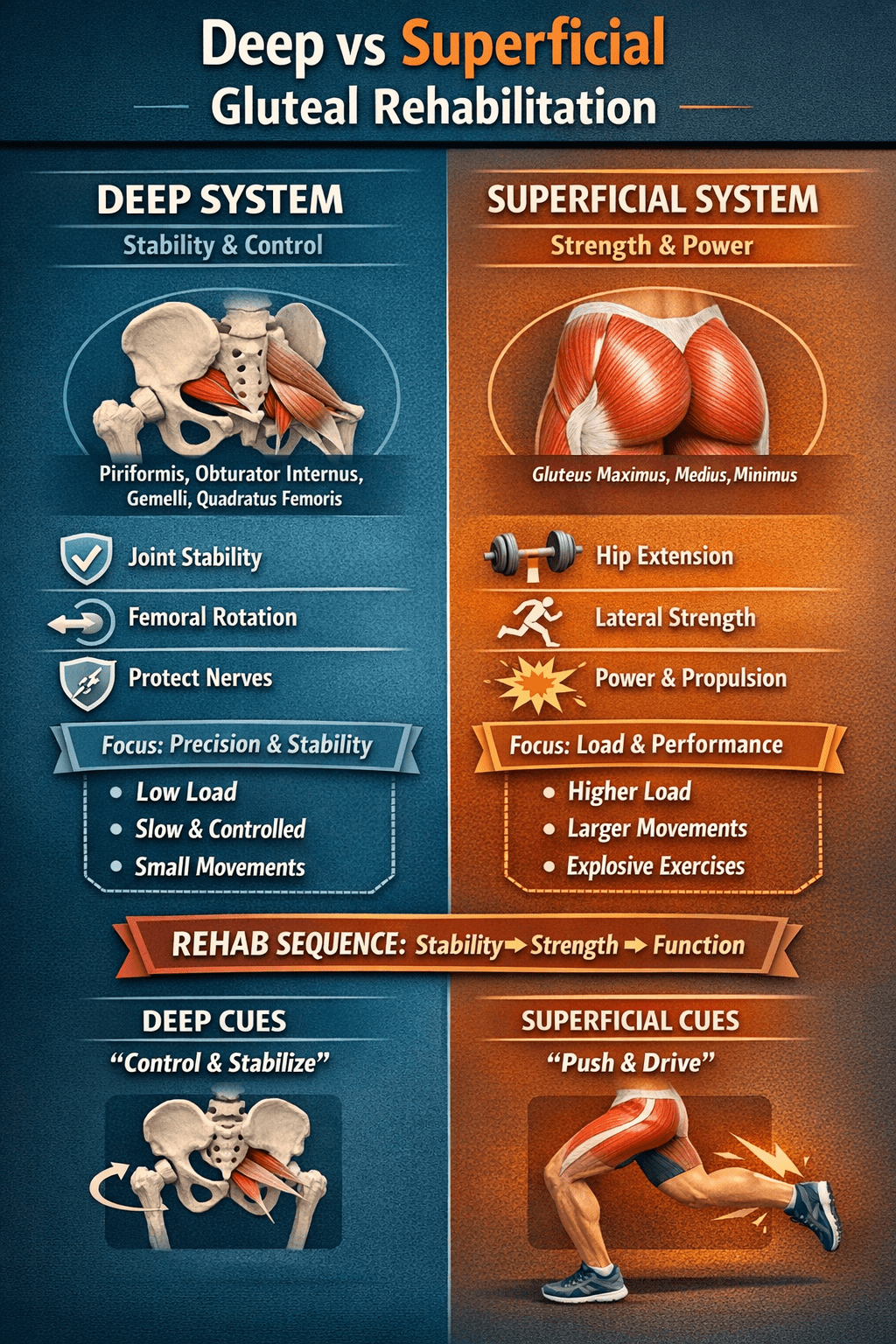

Deep vs Superficial Gluteal Rehabilitation

Why Strength Alone Doesn’t Fix Hip, Groin, or Running Pain

Gluteal rehabilitation is often talked about as if all glute muscles behave the same. In reality, they do not. The glutes function as two distinct systems, each with a different role in movement, injury, and recovery. Understanding this difference explains why some people feel “strong but still sore,” and why rehab sometimes stalls despite good gym work.

In this article, I’ll explain the deep gluteal system and the superficial gluteal system, why they must be trained differently, and how this applies to runners, groin pain, and chronic hip problems.

The Two Gluteal Systems Explained

The Deep Gluteal System: Stability and Control

The deep gluteal muscles include the piriformis, obturator internus, superior and inferior gemelli, and quadratus femoris. These muscles sit close to the hip joint and act primarily as stabilisers, not power producers.

Their main jobs are to:

- Control femoral rotation

- Maintain hip joint centration

- Stabilise the pelvis during single-leg stance

- Protect nearby nerves, including the sciatic nerve

Because of this role, the deep system responds best to slow, precise, low-load exercises. Importantly, these muscles are highly sensitive to position and often switch off after pain, surgery, or prolonged compensation.

As a result, simply “strengthening the glutes” rarely restores deep control.

The Superficial Gluteal System: Strength and Power

In contrast, the superficial gluteal muscles include gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus. These muscles generate force and propulsion.

They are responsible for:

- Hip extension during walking and running

- Frontal plane stability

- Power production and shock absorption

These muscles respond well to load, resistance, and larger movements. Exercises such as squats, lunges, step-ups, and hip thrusts primarily target this system.

However, when the superficial system works without deep stability, it often compensates aggressively. Over time, this can increase strain on the hip flexors, adductors, and pubic structures.

Why Stability Must Come Before Strength

Many people with hip, groin, or running pain already have strong superficial glutes. Despite this, they still experience symptoms.

This usually happens because:

- Deep glute control is missing

- Hip flexors become overactive

- Adductors compensate under load

- Movement looks strong but leaks stability

Therefore, loading the superficial system too early often reinforces poor patterns instead of correcting them.

In other words, strength without control does not equal resilience.

How This Applies to Runners and Groin Pain

In runners, especially those with chronic groin strain or osteitis pubis, hip flexor dominance is common. Scar tissue, pain history, or altered mechanics can cause the body to rely excessively on the front of the hip.

When this happens:

- Deep glutes fail to control rotation

- Adductors overload during stance

- Symptoms linger despite rest or strength work

For this reason, effective rehab focuses first on restoring deep glute and adductor control, then gradually reloading the superficial system.

How Rehabilitation Should Progress

Step 1: Restore Deep Control

Early rehab prioritises pelvic stability, femoral control, and quiet movement. Exercises are slow, precise, and pain-free.

Step 2: Add Superficial Strength

Once control improves, strength work becomes more effective and better tolerated.

Step 3: Integrate Into Function

Finally, rehab progresses into running-specific and single-leg tasks, ensuring stability holds under fatigue and speed.

This sequence allows strength gains to transfer into real movement rather than breaking down under load.

The Key Takeaway

Deep gluteal rehabilitation restores control.

Superficial gluteal rehabilitation restores power.

When rehab respects this order, outcomes improve, symptoms settle faster, and movement becomes more efficient and resilient.